Editorial

Building a national movement after Ferguson

This editorial introduces the fourth issue of the journal of

the Black Left Unity Network. The first three issues have solidly made the

point that there are organizations committed to building unity to create a

solid core for the rebirth of the Black Liberation Movement in the 21st century. There is a radical Black tradition in the US and throughout the

African Diaspora as the historical basis we can stand on for the fight we must

wage today. As of Fall 2014 it is clear that attacks and fightbacks are jumping

out all over the place, coast to coast. In each location there is a cry for

unity and yet we know that local struggles can at best create conditions for

some reforms, but no real fundamental change. Nor can local struggles be

sustained facing the usual ebb and flow of struggle going hot and cold. We need

each other. We need a national movement. Nothing short of a revolutionary

movement will do.

The BLUN is a network of organized forces and militant

individuals. We share our ideas and practical experience toward greater

coordination of our struggle. Right now there is national focus on Ferguson,

just as there was national focus on the case of Trayvon Martin and before that

Oscar Grant. While we fight every day in our local areas it is when we link to

the national hot spots that we can all advance together and raise the level

each time we go forward. In this editorial we want to suggest why we need to

build unity for a new national level of resistance to oppression, how to make

the Ferguson fight back a launching point, and the path to make this happen.

There are four articles in this issue from the African

Diaspora – Africa (Ernest Wamba dia Wamba), the Caribbean (David Abdullah),

South America (Charo Mina-Rojas), and Europe (Gus John). African peoples are

under attack all over the world. Each article demonstrates that our experience

is no different from the general global trend. We are all in need of rebuilding

our movements and finding ideological and political forms of consensus that can

help us produce mighty waves of struggle, unity of action on a national and

international level.

In general, the international situation is diving deeper and

deeper into crisis.

- The global economy has not recovered from the melt down of 2008. In fact

the capitalist state covers over this by lying about the statistics of

unemployment, underemployment, and stagnating wages. The top 0.01%,

billionaires, continue to ravage each economy and drive more and more people

into despair.

- This extreme polarization of wealth has led capitalist states led by the

United States to pursue a policy of permanent war against the third world,

Asia, African and Latin America. The US is particularly guilty of war crimes

against humanity. A major example of this is that the US continues to give

massive support to Israel in its genocidal war against the Palestinian people.

- There is massive surveillance ending any semblance of privacy and

bringing the demonic state of Orwell’s 1984 into existence. Big Brother lives

in the White House, CIA, NSA, and the Pentagon. Global media serves not as a

basis for democracy but as a propaganda arm of the global capitalist class.

On a national level in the US this global crisis is anchored

in every aspect of life, especially for Black people.

- Permanent war has hit the streets in the US. The Pentagon has

militarized local police departments with billions worth of military arms, and

turned over training to the Israeli Defense Forces as was the case in Saint

Louis County hence impacting Ferguson!

- The class polarization continues with 95% of the income gains in recent

years going to the top 1%. Also white family wealth is just under $100,000 but

for Black families it is just under $5,000!

These are some of the conditions that set the stage for a

spark to ignite an outbreak of resistance, and as we all know, “A single spark

can start a prairie fire.” (Mao) We had a spark with Katrina. We had another

spark with Jena Louisiana. The murder of Trayvon Martin was another spark. Now

the spark is Ferguson Missouri with the murder of Michael Brown. We have to ask

a very important question: What can lead a spark to start a prairie fire? One

kind of fire is a flash fire that can quickly burn out of control and be

destructive in unintended ways. Another kind of fire burns down intended

targets of opportunity and clears a path for a new future. Forrest fires are natural

and clean out the forest in preparation or new growth. How can the spark of

Ferguson lead to this kind of progressive fire? In the main, we are speaking of

a symbolic fire of mass resistance to oppression, both in the St Louis region

and the rest of the country.

A starting point can be the assessment of the social forces

acting in different ways in the situation. In Ferguson the Black community was

under attack and most forces were moving for some kind of social change. The

Black political class targeted the electoral arena as Ferguson is 65% Black but

mostly led by white elected officials. The traditional middle class leadership

of the civil rights organization and the churches called for peaceful protest

but calm and no direct confrontation and civil disobedience. The organized

trade unions joined in symbolic protests on the stage of the October 10th march/rally

but did not mobilize its membership to lead the militant protests of the

community. The main fight back is coming from that sector of the community most

impacted by police violence, unemployed young workers, the poor, and youth in

general. They have directly engaged the police in street confrontations, but

without a program for change with tactics that move the struggle forward.

Our reflection on the struggle in Ferguson represents two

paths forward – the movement in Ferguson and the national rebuilding of the

Black liberation movement. All forces in the Black community in Ferguson have a

role to play. The electoral struggle will need to be organized and the critical

issue is the role of the middle class versus the workers, youth and poor

people. The masses represent the votes that are needed, but we ask who will

these votes elect? And for whoever is elected, what policies will they advance?

What will their relation to the masses be after being elected? We propose a

five-point program to be part of any electoral campaign:

- Demilitarize the police and put them under an elected civilian review

board

- Livable wages for all public employees

- Legalize marijuana to keep Black youth from jail time for such offences

- Use eminent domain to seize abandoned homes to house the homeless

- Reduce all traffic fines to a low level with no jail time attached

But we know that this reform agenda will not end the suffering

and pain of the people who will need a more militant and radical program. Frequently

what we initially think of as change is a reordering of the system of

oppression. We need a society in which everyone has a job, a home, health care,

life-long education, and plenty of time for rest recreation and cultural

creativity. For this we need a revolution, and for this we need a national

movement.

Building out from the hot spot of Ferguson should lead to

rebuilding the Black liberation movement. First we need to connect the

activists fighting in different locations against similar cases of police

violence. This has certainly been the contribution of October 22nd. We also have

many other battlefronts to connect up. All of these reform struggles need to be

connected to the Black left. These individuals and organizations are advancing

ideological leadership to envision and fight for a post capitalist fundamental

reorganization of society. Our movement is the cauldron for embracing the

dialectical unity of reform and revolution. This combines the tactics of the

day-to-day struggle of what we are fighting against with the long term

strategic vision of what we are fighting for.

Building a movement is more than the spontaneous outbursts

of fight back. We need sustainable organizational coordination and that means a

higher level of discipline and consciousness. We are called upon to study and

build collective processes. This requires us to go beyond our comfort zone of

what we agree with to critically and carefully embrace all of the progressive

tendencies in our movement. We need to understand each other and not rush to

judgment based on ignorance of what each of us stands for. That would be

repeating an error of the past. To begin this process the BLUN has developed a

draft manifesto for consideration by all of the forces interested in rebuilding

the Black liberation movement.

DRAFT

MANIFESTO

FOR BLACK LIBERATION

The deep crisis facing Black people requires bold radical

action. We can accept this challenge as individuals and as groups, but the

strategic goal must be the rebuilding of a national movement for Black

liberation. There are many groups, small and scattered even when organized on a

national level. We are in the hundreds of thousands on an individual level of people

who see the need for militant fight back. It is time for a great coming

together to rebuild our Black liberation movement on a national level. This

manifesto is being presented to you as a draft that we can all debate and make

whatever revisions are necessary. We need to be on the same page and channel

our efforts into one mighty fist that can strike decisive blows against our

oppressors.

Our fight has always been for freedom

The history of Black people involves every aspect of life

but there has always been a central theme, how can we get free. This is a

critical starting point for all education and self-consciousness in the Black

community. It demonstrates the basic humanity of Black people, the will to live

and find ways to improve the quality of our lives as a collective, a community,

a nation. In order to be a revolutionary you have to know your history.

We have a Black Radical Tradition to build on

Our tradition of militant fight back has been anchored in

five ideological tendencies that are most often woven together in the thought

and practice of any given individual, organization, or movement. These are:

Black liberation theology, Pan-Africanism, Nationalism, Feminism, and

Socialism. The most recent concentration of ideological discourse and debate

has been in the 1960s represented in the thought, life and work of Martin

Luther King and Malcolm X. In order to be a revolutionary you must study this

radical Black tradition.

We are rebuilding the Black Liberation Movement

There are many ways to identify when we have had a national

Black liberation movement. The main point is having a high level of unity of

the militant forces actively organizing and mobilizing at local levels. Moreover,

this goes beyond single issue movements and grasps the overall character of

fighting on all fronts. When we have had a high level of our national Black

liberation movement we have had policy formation by bodies of national

representation, coordination of national campaigns of struggle, and major

conferences in which ideological debate led to consensus and an intensification

of resistance. This refers to the 1967 and 1968 Black Power Conferences, the

1970 Congress of African People, the 1970 revolutionary peoples convention of

the Black Panther Party, the 1972 Gary National Black Assembly, the 1974

conference of the African Liberation Support Committee, and the 1998 Chicago

launching of the Black Radical Congress. In order to be a revolutionary you

must study these advanced stages of our national Black liberation movement.

We are the Black Left Unity Network (BLUN)

Based on the lessons of these major conferences and the

intensification of the capitalist crisis it has become clear that the Black

liberation movement has to be rebuilt on the basis of the fighting capacity of the

masses of working and poor people who are the vast majority of people in the

Black community. This manifesto is being developed by the BLUN in order to

recruit people and organizations who understand that racism and national

oppression can only be ended by waging a Black working-class led struggle in

which the capitalist system is targeted as the main enemy of Black people,

indeed all of humanity.

The BLUN has been in motion for the past seven years

networking with individuals and organizations, building unity and joining every

struggle that emerges. Our greatest advance in the last two years has been our

journal, The Black Activist. This journal represents the kind of unity dialogue

that we hope to spread. It begins the general theoretical work that can

educate, motivate, and agitate for greater development of the national Black

liberation movement that we need.

We are building the BLUN as the organizational framework for

all Black revolutionary militants to come together to discuss our ideas, to

coordinate our struggles, and to mobilize the vast majority of our people in

the fight back that is necessary to oppose and defeat our enemies. To deepen

the unity and context of revolutionary struggle, we must get the necessary

criticisms from our comrades based on the principle of unity-struggle-unity.

Black History is the fight for freedom

The lessons of history are general summations of a process,

and can be about individuals and social groups, from the local level to the

entire world. This process includes social forces that represent different

classes and nations, as well as many other aspects of humanity (gender,

sexuality, religion, generations, etc.). The main dynamic of the African

American experience, the theme that embraces all Black people, is the fight not

only to survive but to resist and end capitalist exploitation in whatever form

it has been developed, from the slave trade and colonialism in Africa and

throughout the African Diaspora, through sharecropping, industrial wage

slavery, and now being damned to excruciating forms of poverty. The system has

been against us but we have always fought back, and the fight back is the great

theme of our history.

Africa

Africa was invaded by Europeans. They gave Africa a double

blow – they stole the people and forced them into the labor systems of slavery

in the West, and they colonized African land and virtually enslaved the people

who remained in Africa. In both instances they imposed European culture on

African people, especially language, religion, legal systems, what little

education that was provided, and cultural aesthetics. The famous colonization

frenzy was legalized in the Berlin Conference of 1894-95.

After World War II African resistance movements expelled the

invaders and created independent African countries beginning with Ghana in

1957. These countries were mainly guided by a rising African capitalist class

who compromised the liberation struggles by aligning their policies with the

World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Many African revolutionaries

who represented the working class and struggles against capitalist

neo-colonialism were murdered (e.g. Patrice Lumumba, Chris Hani, Amilcar

Cabral, Edwardo Mondlane, Pierre Mulele, General China, Kimathi, Stephen Biko,

Maurice Bishop, Walter Rodney, etc.). Today Africa is facing the need for a 21st century revolution led by the working class and its impoverished masses.

The European Slave Trade

The process of raping African of its population was to serve

the labor needs of Europe, especially in the fields and mines of the Americas. As

Eric Williams explains this was a triangular trade that served to link Europe

(manufactured goods) to Africa (Labor) to the Americas (extraction of raw

materials). This barbaric process spread Africans to every island in the

Caribbean and to every region of North, Central, and South America creating the

African Diaspora.

The freedom struggle raged against these crimes against

humanity. Strong examples are Queen Nzinga Mbande of Angola, Joseph Cinque of

the Amistad Revolt, the revolts led by Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey, Gabriel

Prosser and the freeing of the slaves from the plantations by Harriet Tubman.

The Slave System

Slavery was a labor system that bread, sold and worked

Africans to death, lasting about 400 years! Millions of Black people were

spread throughout the south to produce tobacco, rice, and many other products,

especially cotton. Black field hands were worked to death in a system from

“Can’t see to can’t see.”

It was the economic process by which the wealth of the

ruling class was created that continues through inheritance and corporate

profits till the present day. The production of cotton pulled Black people into

the deep-south creating the “Black belt.”

Emancipation

As result of the two labor system – slavery in the South and

wage labor in the North – there was struggle over the control of the federal

government. This struggle led to the Civil War. Slave labor threatened the

wages of white workers, and, added with the moral imperative to oppose this

vicious system advocated by the Abolitionist Movement, this motivated the

masses of people in the north to support the war.

Black people were not given freedom by anybody. They rose up

and fought in many ways to be their own liberators. DuBois in his master work Black

Reconstruction discusses the general strike of slaves withholding their labor

and undercutting the slave regime. Black people fought in the Union Army at

numbers (per cent of total population) far higher than whites. Further during

Reconstruction Black voters and elected officials played a dramatic role by

democratizing the south including free public education for everybody that had

not existed.

The African American Nation

Within the Black belt Black people began to create African

American culture that was a continuation of but different from their original

African cultures. They created new social institutions, forms of

speech/language and collective community life that were demonstrated in the

church, musical and other social and political venues. They were concentrated

in counties that were majority African American, dominated by the plantation

economy, repressive county and state governments and a system of apartheid.

The modern Civil Rights Movement developed in opposition to

the barbaric oppression imposed on Black people in the Black Belt, from

lynching to peonage.

Dispersal to Proletarianization

During the 20th century there was a push out of

the south and pull into the North (West, Midwest and East) that dispersed Black

people into the major cities of industrial development. Black people were

forced out of the rural agricultural South into the urban industrial North.

Migration out of the South was forced through racist terror

as well as an act of resistance in that people were rejecting old forms of

oppression in search of a better life.

Urban Ghettoization

Racist segregationist practices dominated the cities and a

real estate conspiracy forced Black people into the worst housing, areas that

concentrated all of the worse social problems usually under tight police social

control. The major transformation was based on Black people being employed in

the industrial system and on that basis building from their southern roots into

major bases of potential political power.

Crisis of Permanent Poverty

A technological revolution is reorganizing the basis for

society, including dramatically reducing the demand for the labor of the old

industrial system. The capitalist state is realigning and ending the social

safety net brought about by the struggles of the 1930s and 1960s that force the

FDR New Deal and the Great Society of Kennedy and Johnson.

A growing section of the Black community is being forced

into permanent poverty, under the chemical assault of drugs both illegal and by

prescription, and facing a new form of slavery in the prison system.

Our main fight is against the capitalist system

The Black left is fighting on all fronts against all forms

of oppression. A central point of unity is that all of our struggles can

advance only to the extent that we mount a full assault on the capitalist

system. Capitalism is the basis for the 1% control of this society and the

source of our misery.

What is Capitalism?

Capitalism is an economic system that exploits the labor of

the working people and feeds the greed of the corporations and the rich who own

the factories and machines. People work and create value turning raw materials

into usable products and are paid much less than the value they create, only

the minimum. Most of the rest is surplus taken by the corporations as their

profit. There is a struggle between the workers and the owners over the

allocation of this surplus – they live fat while we starve.

How is the origin of US capitalism based on slavery?

The wealth needed for the origin of the industrial system in

the US was created out of the super profits taken from the sale and labor of

the slaves, especially in the cotton fields. This slave based wealth has been

used to fund many major corporations and banks, and the basis for wealthy

families that maintain control over social and cultural institutions like the

major private universities, especially in the Ivy League.

How does capitalism exploit us?

Today we live at a time when capitalism is transforming and

increasingly replacing human labor with smart machines. If people are not

working for a wage the market system is dysfunction for the circulation of

goods and service – no money means people can’t buy what they need.

Capitalism has turned to making money on death, including

the combination of bad food and bad health care, all varieties of drugs and

alcohol, TV culture that kills the mind and the military industrial complex

that produces major weapons for imperialist wars and all forms of military

aggression including the violence in the cities throughout the U.S. All too

often our churches become appendages to the capitalist system by preaching

money over morality.

How does capitalism exploit the world?

Using global organizations like the International Monetary

Fund (IMF), the World Bank (WB), and the World Trade Organization (WTO) among

others, the global capitalists have invaded almost every country in the world

to capture cheap labor and important raw materials. This continues the

imperialist practice of moving wealth from the third world into the major

European countries and the US.

The United Nations and NATO are used to justify imperialist

military aggression.

Can we defeat the capitalist system?

Nothing lives forever – slavery ended, feudalism ended, and

capitalism will end as well. More and more the majority of humanity has no

stake in the capitalist system and is rapidly growing to hate it. Outside of

the US the discourse of resistance is explicit in its rejection of capitalism,

but inside we face the soft terror of media and government obsessed with

putting a gag rule on any alternative discourse. A good indication of the

rejection of capitalism was the “Occupy Movement” that exposed the evil

exploits of the ruling 1%. The end of capitalism will only come with our

militant unity of action.

Strategic working-class unity starts with the leadership of the Black

working class

Why the working class?

The majority of people in the US are working people, all of

whom are being exploited by the capitalist system and they hate it. The

greatest allies of the Black Liberation Movement are the militants in the

working class movement, especially from the oppressed nationalities and

peoples. The enemy of my enemy is my friend. Of course there is a racist

national chauvinism that turns some white workers into enemies of Black people

under the false notion amplified by the mainstream media that we are the cause

of their misery. As people fight in their own interest against the bosses, the

conditions are created to expose the role of white supremacy, offering

opportunities to win significant numbers of white workers to an anti-racist

working-class unity. This is meaning of the slogan solidarity in the workers

movement.

What was the connection between Black slaves and white

workers

When Black people were picking cotton in the slave system

the capitalist bosses chained white youth to machines in the textile industry

to work the cotton into thread and cloth. Slaves worked side by side with white

workers, both exploited, but whites confused by the paltry white skin privilege

of a little more pay and the opportunity to join in the oppression of Blacks.

Black workers organizations

The first Black worker organization, The Colored National

Labor Union, was formed in 1866 and included Frederick Douglass as one of its

early leaders. High points in the organization of Black works have been the

League of Revolutionary Black Workers (1969), Black Workers Congress (1971),

Coalition of Black Trade Unionists (1972), Black Workers for Justice (1981),

and Black Workers Unity Movement (1985). There are also many rank and file

Black caucus groups, workers centers, and now the Southern Workers Assembly.

Class unity with Latinos

National oppression and extreme capitalist exploitation of

Latinos makes them close allies of Black people. This is especially true with

the people who share a heritage from Mexico, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic,

and other countries in the Caribbean, Central and South America.

The capitalist strategy is to divide workers and play them

against each other. The most desperate will take lower wages creating a

conflict if people lose their jobs. Our class unity must take a strong position

against this capitalist ploy and unite Black and Brown workers in a common

cause.

Class struggle and Black liberation

The fight of workers is first and foremost a fight to make

their working conditions better, higher wages, with benefits and retirement

pension with which they can lead a decent quality of life. People fight as

individuals, work teams, whole work places, and entire industries. All of this

is necessary. We believe we must go further and link these reform struggles

with the vision and preparation to fight to end the capitalist system once and

for all. We are in an all-out war of the capitalists against us, the workers. They

will always cheat us, because as capitalism dictates exploitation is how the

game is played.

We fight on all fronts

The unity of the Black Liberation Movement and the workers

movement under revolutionary leadership does not take place in the abstract. The

class struggle against national oppression always takes place in a concrete

context. It is our theory that keeps us focused on the underlying issues that

unite us against the capitalist ruling class. The system of oppression and

exploitation has set us against each other, propped up people are in between us

and them, and employs the state and its police forces as their pawns of social

control. While in the day to day struggle we confront many “in between” types

it is important to keep our eye on the real enemy. On each battle front it is

useful to maintain a focus on a strategic slogan to guide us.

Women

Black women face the triple oppression of national

oppression, patriarchy, and class exploitation because most Black women are

working people in a racist country run mainly by white and male supremacists.

The movement we need requires gender equality! Mobilize the

women and follow the leadership of women on all battle fronts!

Environment

The capitalist system is destroying the natural environment

of the world by unleashing profit seekers to ravage eco-systems, pollute the

air and water, unleash nuclear waste, create global warming, and rapidly

decrease bio-diversity that has built up over millions of years.

The earth’s resources must be a commons for the use of all humanity

to share! End fossil fuel use! Our future must be green!

Elderly

Our society is growing older but lacks sufficient support

and respect for senior members of our communities. This includes removing them

from trans-generational households and forcing them to face the crisis of

declining incomes, weakening welfare support, poor health care, and isolation

from loved ones and friends. We must become a sharing and loving society from

the cradle to the grave.

Full pension for all retired workers! Build social capital

of the elderly to be lifelong contributors to society! All older people must be

respected and cared for!

Health

The capitalist system has spoiled our food, used advertising

to seduce people to lust for sugar, salt, and fried foods, and turned health

care into a factory system that keeps most of us running to the pharmacy

dependent on the latest drug commodity hoping the insurance company will pay. Of

course there are people with no insurance and have to choose between food,

rent, and health care costs. Look around and see the obesity, bad teeth and

poor vision and hearing. The capitalists have turned our neighborhoods into

food deserts. This has to stop.

Fight for universal health care! Stop fast foods in our

community! Forward to community gardens! Ban liquor sales in our community!

Education

The education gains of the 1960s have been wiped out. Our

children are not learning to read and write and work with numbers in the public

schools while the system takes money out of the public schools to finance the

privatization of education. In many urban areas school boards are closing

schools in the Black and Latino communities at an alarming rate. High stakes

testing results places our youth on a path of failure with limited

possibilities for good employment. College attendance and graduate rates are

not increasing and with attacks on affirmative action and minority scholarship

funding ethnic cleansing of the campus is taking place.

Free universal quality public education for all!

Police repression and prisons

Every 28 hours the police forces in the US gun down a Black

person. The vast majority of Black youth are routinely rounded up and placed

into the data bases of the police authorities. The prisons are overcrowded with

Black men, and Black women are increasing being processed through the prisons

camps as well. Many of the militant fighters have been incarcerated in solitary

confinement for decades. Our communities are under constant surveillance, and

when out of our segregated neighborhoods we are harassed and arrested for

driving while Black or wearing a hoodies, just being ourselves. We are still

not free in this country!

Release all political prisoners! Stop the surveillance and

monitoring of all communication of the Black community! Stop police murder!

Community control of police!

Housing

The last few economic crises that have ruined people’s lives

in this country have targeted Black people most of all and many have been based

on housing exploitation. Whether it is outrageous mortgage schemes, or loan

programs that cheat the unsuspecting consumer, or the reservation camps of

public housing, Black people are facing housing insecurity. And when housing is

found it is usually the poorest in quality and highest in cost. We are faced

with an increasing number of people who are homeless, including adults and

children.

House everyone and eliminate homelessness! End loan

practices that cheat the people!

LGBT

One of the dangerous practices that undermine democracy is

devaluing and punishing people who fit into a category that is defined as bad. This

has all too often been applied to people with varying gender styles of life,

sexual orientations. Everyone must be guaranteed fundamental rights of all

people. Same sex relationships and other gender based behaviors must always be

respected. It is crucial to link the fight against LGBT oppression to the

cultural crisis of the capitalist system.

End homophobia now! Let marriage be a personal choice!

Culture

The capitalist system turns everything into a commodity to be

bought and sold, and this includes the cultural production of the community. We

all used to sing and now we buy CDs and pay to go hear other people sing. Furthermore

they pay them to sing what they want not what we have been doing to serve

ourselves and our community. Hip Hop – Rap was invented to serve our community

and expression the political critique and aspirations of the youth and has been

twisted into the abnormal gangster rap. Perhaps the greatest danger comes from

TV and its renaissance of the old stereotypical images of Black people as

clowns or gladiators.

On the other hand there is an unbroken history of cultural

production that has inspired people to resistance and fight back. The poets and

musicians lead the way. Our cultural revolution must re-link to our African

origins and embrace the best in the history of our cultural developments as

African Americans. Jazz is Black classical music.

Cultural production for Black liberation! Recruit cultural

workers to every front of struggle!

Reparations

The exploitation of Black labor and the brutal oppression of

Black people is part of the international conditions create by the

Trans-Atlantic slave trade and system of colonialism. This international system

created a major part of the capital accumulation for the development of

European and U.S. capitalism. Issues of underdevelopment, lack of opportunity,

inequality in social status, and shorter life expectancy for the majority of

Black people throughout the world, are some of the injuries built into the capitalist

system with continuing impacts. The demand for reparations connects Africa and

the African Diaspora to a common international demand of redress against the

governments of colonialism and imperialism and the international economic

institutions like the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and the World

Trade Organization for crimes against humanity as outlined in the UN

Declaration on Human Rights.

Reparations must be one of the major demands for

self-determination!

The centrality of the South

The Black liberation movement takes place in every state,

every city, and has tasks in many countries around the world. Special

consideration must be given to the ancestral homeland of Black people in the

US, the former slave states of the South. This is the largest concentration of

Black people, the greatest levels of exploitation by US and global capital, and

is leading the country in right wing initiatives.

Concentration of Black people

In 2010, 55 percent of the black population lived in the

South, and 105 Southern counties had a black population of 50 percent or

higher.

Concentration of class exploitation

Throughout the 11 states of the Southern Black Belt, there

are 11,523,063 people living in poverty. A single parent of two children

working a full-time minimum wage job will make $10,712 before taxes—more than

$4,500 below the federal poverty line.

Global capital

Because many Southern states have right-to-work anti-union

laws the region has recruited global capital to take advantage of cheap labor.

Right wing political concentration

The most backward politicians with anti-democratic policies

are based in the South. Their demand for state’s rights is a form of autonomy

to keep the South as a region

We are part of a global struggle

We all live on planet earth and increasingly our struggles

involve issues that impact people all over the globe. We embrace the need to be

internationalists and focus on freedom and quality of life for everyone in the

world. Our approach is to link especially to the struggles in the African

Diaspora.

The struggle in Africa

1960 was proclaimed by the United Nations as Africa Year

because so many countries were gaining their independence from European

colonization. However this led to neo-colonialism governed by the World Bank

the IMF. Furthermore a class of bureaucratic tyrants took control of the state

apparatus in most countries and looted the wealth and suppressed the people.

Rebuild the African struggle for independence, unity and

freedom!

The struggle of Black people in the Caribbean

All of the Caribbean island countries are part of the

African Diaspora. In their origin the difference for African people was only

about where the slave trading boat stopped and which European colonial language

one was going to be forced to speak. The fight continues in the Caribbean on

many levels, from the trade union based Movement for Social Justice in

Trinidad-Tobago, to the fight for sustaining socialism in Cuba.

Long live Caribbean unity! Oppose the domination of US and

global capital!

The struggle of Black people in Latin America

In Central and South America, including Mexico which is in

North America, their history of Spanish colonialism brought African labor and

historic Black populations. This is notably in Brazil and Colombia, but there

is some manifestation in most places. The impact of US imperialism has forced

many of these peoples to migrate to the US creating Latin American Diasporas. We

have the joint unity of the origins of the African Diaspora and the

contemporary shared experiences of racism and class exploitation.

Long live African American and Latino unity! Build our

movements of movements throughout the Americas!

The struggle of Black people in Europe

There are Black communities all over Europe. They have been

informed by the militant struggles we have waged in the US and we must embrace

their history of struggle as well. They face comparable forms of racism and

class exploitation, those born there as well as the recent migrants from the

African continent.

Long live the unity of African Americans and Black Europe!

Our fight for reform is linked to a revolutionary strategy

The idea of a revolution is abstract but the fight for one

is not.

The day to day struggle

Peoples fight back in the context of their lives, at their

place of work, at the unemployment office, at the grocery store, the school,

the church, etc. Big political ideas take shape and form on the ground in

practical circumstances. When the fight intensifies everybody can get educated,

can get political, and can begin to think about the link between the reform

struggle and the revolutionary leap that is necessary. It is mainly in this

context that a Black left can be grounded in the roots of our people, in the

very fight they wage themselves. We join them, embrace their leadership, link

their fight with the fight of others, and help them to sum up and learn lessons

from victories and defeats, and train militants to increase their ability to

sustain the struggle.

Fight back every day! Link the fight for reform to revolutionary

goals!

The response to racist attacks

Every racist attack must be opposed and mass resistance

built to end it. Just as we raised the slogan “No More Trayvons” as part of the

massive nationwide mass mobilization, so we continue that on higher and higher

more coordinated levels. This is one of the key tasks of building a national

Black liberation movement.

The electoral struggle

The capitalist state is a rigged game controlled by the

ruling class. They don’t play fair and we can’t win by getting in it and trying

to reform things. All too often we have been lured into local politics as

mayors and city council officials only to try and fix a broken system that

can’t be fixed with minimal reforms. However electoral politics is a terrain of

struggle in which debate and discussion can be used to raise the consciousness

of people and present them with an alternative to the hypocrisy and illusions

of mainstream politicians. The movement must remain autonomous from the state

and NGO control. On the other hand Black power at the local level can be used

by the movement, especially if used to build the independent power of the

forces in struggle – unionization, minimum wage, use of eminent domain to house

the homeless, money for public schools not charter schools, etc.

Hold elected officials accountable to serve the community!

Our struggle will last for generations

Each of us lives a life and we hope to attain the goals we

set during that time. It is important to think of struggle as a handoff through

the generations in which each generation has a mission, a contribution to make,

and then it is up to the next generation to take it from there. We all fight

for freedom, but the fight towards freedom goes forward one step, one stage,

one historic leap at a time.

The 1960s generation

The last great upsurge was the 1960sSee “How the 1960s’

Riots Hurt African-Americans,” National Bureau of Economic Research. The

activists of the 1960s are the current elders of the movement. They are walking

living libraries of information. They are also the bearers not only of the

experiences of victory and great mass mobilization but of past factional

battles and splits within the movement. All of this experience is valuable,

both what to emulate and what to avoid.

The 21st century

The 21st century is very different from the 1960s.

We are in the midst of a technological revolution that is being used to change

all aspects of life and we have to adapt to that and learn how to use digital

tools to make our struggle more effective. We don’t have the revolution of

rising expectation that we had in the 1960s, fueled by the revolutions in China

and Cuba as well as the national liberation battles all over Africa, including

Vietnam. Today we are fighting many forms of Afro-pessimism as well as the

disease of drugs and a breakdown of many traditional institutions. Today we are

being challenged to rebuild on a new basis to take our fight to the next level.

Building revolutionary institutions and rituals to

sustain our movement

Our task is to build organization to struggle in every

context – workers, students, church members, residents, health care patients,

seniors, etc. People get reborn when engaged in struggle and we must engage as

our people need a rebirth. Every organization must be built on the foundation

of our own people and not based on hand outs from friendly foundations and

NGOs.

Dual power: A strategic revolutionary objective of self-determination

and workers power

Altering the balance of power between the Black and

multinational working-class and the U.S. ruling-class and its imperialist state

in favor of positioning the oppressed and exploited masses for social

revolution, must be a constant aim of revolutionary strategy.

A strategic program focuses mainly on the relationship between

politics and economics. It must not only put forward demands for democracy, it

must fight for transformative power to organize alternative social, economic

and political models that begin to engage the masses in organizing and

administering in a different way the places where they work, the communities

where they live, the social institutions they rely on and positions in local

government. This can be defined as a level of dual and contending power.

Our pledge is to fight for freedom by any means necessary

The BLUN is committed to building a national network of the

most militant, most class conscious fighters for Black liberation. Our goal in

drafting this manifesto is to create a national dialogue about what basic unity

we can reach so that we have a context for coordinating our fight back. This

Draft Manifesto will be discussed on conference calls, in face to face regional

meetings, and at a National Assembly for Black Liberation. It is a draft so we

welcome all comments, criticisms, and revised text.

RETHINKING

BLACK LIBERATION IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA

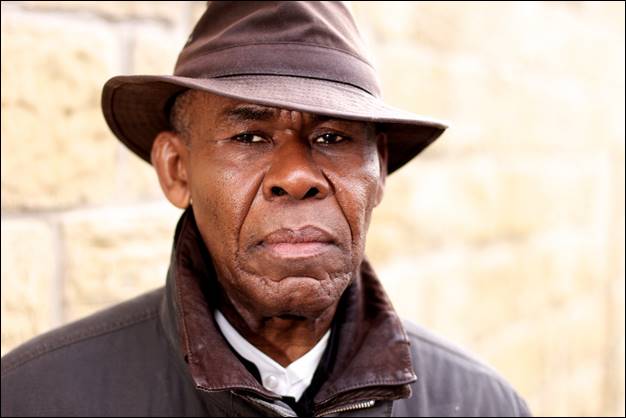

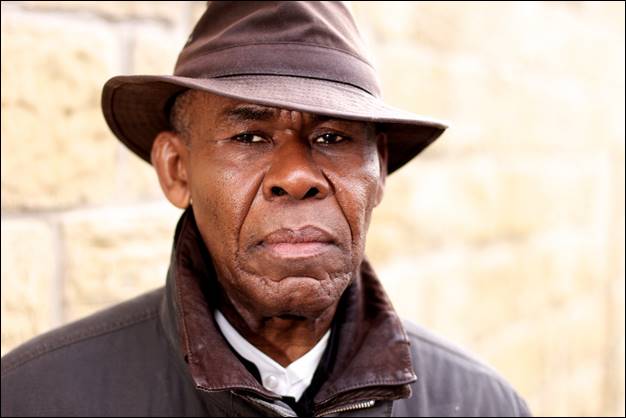

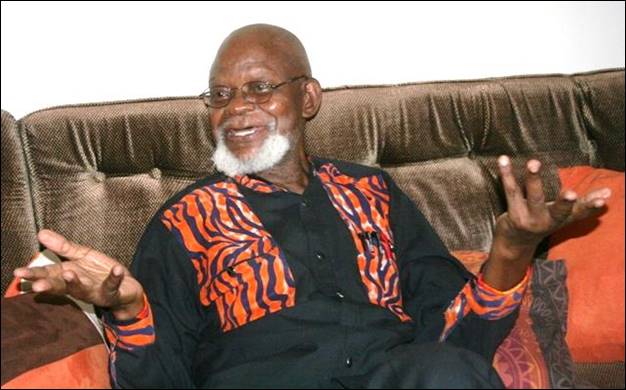

03 Africa: Reflections on African Renaissance

by Ernest Wamba dia Wamba

[1]

From http://www.thehabari.com/habari-tanzania/profesa-drc-amuunga-mkono-rais-kikwete

The situation in Africa is not good. Despite the hopeful

signs of relatively high rates of growth—mainly in the service sector and the

extraction industries—in general, the situation is not good. It has not been

good, for some time now in some countries.

Are alternative paths of development still an option for African countries

today?

Those types of questions are no longer often posed because

there are not enough political subjects in those countries that could raise

them: Berlinist African states (carved after the Berlin Conference 1884-5) have

now the sole desire to be under the umbrella of the Empire. When the world was

divided into two, that is up to 1989 or so, discussions on the non-capitalist

path to development, the African socialist path to development, or even the

scientific socialist path to development were taking place. Some forms of

planning structures existed in some countries. The Breton Woods Institutions,

among others, have since taken over the “planning” of those countries’

economies.

The whole world, however, seems to be pressed for the need

of alternative paths of development. We can differentiate negative pressures

and positive ones. Among the negative ones we can mention the health of Mother

Earth. Global warming causing climate change is very much affecting that

health. This is due to the capitalist path of development based on the

destruction of relations favoring healthy ecological reproduction.[2] What used to be

strong beliefs such as that Earth can heal herself or that science and

technology will help us heal Mother Earth are dwindling. It is clearer and

clearer that survival on this planet may be jeopardized if the world continues

on the same capitalist path of development.

The shift in the paradigms on which capitalist path was

founded, namely the Enlightenment philosophies and world views—concerning the

linear conception of history, the conception of Nature, the belief that if

people follow their self-interest this will lead to the greatest common good,

etc., is another pressure for change. Capitalist forms of property are

curtailing world political will to urgently address the problems.

With the financialization of the world economy[3] fewer and fewer

people, the 1% or less of the world population through the financial market

dominating other markets, control the economy in a very irresponsible way such

as entertaining fiscal paradises and refusal to pay taxes. They have come up

with neo-liberalism and the so-called ‘less state, better state’ favoring their

egoist interests and marginalizing those of the majority of population—such as

education, health delivery services, transportation, etc. They thus resist

change. Mass uprising and sit-ins, etc. have been targeting them and exposing

them. Secret societies, through which that minority is often organized and

making decisions affecting the entire world in the pursuit of its egoistic

interests, for example promoting for wars as a quick and sure way of

self-enrichment, are being also exposed.[4]

Western democracy, especially the way it is exported to the

rest of the world, has been increasingly critiqued in the mass uprisings

agitating for new forms of democracy and politics. Expressions of societal

decay are also rising; throughout the world people are demanding for

fundamental change and for dignity.[5] Crises faced by the West are very instructive for the people of Africa. Due to

the financial crisis Europeans are now facing, the latter certainly understand

now, we believe, what a painful experience Africans faced with the past

structural adjustment.

The global African family(Africans from the continent and

the Diaspora) has contributed a lot through their struggles and lessons drawn

from them against oppression, exploitation and humiliation—the most humiliated

group in the world—for human dignity; capitalist development, in the main, has

failed to guaranty such dignity . Struggles against all forms of slavery and

against colonialism, for example, have given rise to forms of healing practices

and politics and spiritual renewal—such as the Lemba movement and prophetic

movement and politics in the area of Kongo Kingdom—with universal appeal to

deal with the capitalist caused afflictions on individuals, families or

communities.[6] However, agitation and debates over reparations have not yet produced anything.

Africa, in the main, has been forced to remain an economy based on extraction

industries (of material and human resources—including hidden forms of slave

trade-sexual slavery.) In general, capitalist path of destruction for

development has been linked to wars and genocide (physical extermination

genocide and cultural genocide).[7] Those are few negative pressures in favor of an alternative path of development.

There are also positive pressures on humanity to have

alternative paths of development. The late scientific and technological

revolution requires new modes of societal organization. We are witnessing a

convergence of new technologies: information technology, genetic engineering,

biotechnology, cognitive technologies and robotics, etc. These are opening up

new ways of acting in society—that would not necessarily be enhanced by

capitalist relations of production and their conditions of existence. In fact,

capitalist exploitation of these new scientific forces may give rise to certain

dangers. Jaron Lanier,[8] for example, argues that the internet has destroyed the middle class claimed to

be the basis of Western democracy. Thanks to some of these technologies, the

African youth is developing independent forms of relating to each other,

creating some space of freedom more or less outside of the space of state

command.

Important paradigm shifts in science, especially with the

discovery of the holographic universe[9] as the best scientific concept of reality, show that many things are needed to

be changed including certain long lasting habits and beliefs. A better

understanding of the human energy field, explaining for instance what used to

be called abnormal phenomena, may allow us to organize society in more humane

ways. Advances in sciences are allowing the rediscovery of spirituality.

The astrophysicist, Dieter Broers, in his book, Solar

Revolution,[10] shows that increased activities of the sun have been inducing an extension of

the Earth magnetism leading to an expansion of human consciousness. This will

equip humanity with better abilities to deal with the problems it now faces. It

has been predicted that exceptional children will be born.. Those children will

be equipped with clairvoyance, clairaudience and healing powers by touch. I

have seen one such a type of children in the DRC; his powers of clairvoyance

and clairaudience are impressive. A report on the internet[11] showed that

there exist quite a few of those children in the world. Of course, this is

still within the range of hope. And, in a sense, it would be a form of Earth

self-healing. But, it stirs our imagination to think bold possibilities.

Studying conditions for effectiveness and excellence in business

as well as in life, Stephen R. Covey has, in his book, The 7 Habits of Highly

Effective People,[12] identified 7 habits which seem to be hampered by some capitalist forms of

competition; solidarity( including sharing) seems to be a major condition for effectiveness

in life.

Using the knowledge provided by the new sciences and

technology, especially the refined techniques made possible by those sciences,

techniques which facilitate the detection of very high frequencies in the human

energy field, the Congolese scientist, Longa-Seno,[13] was able to

study the connection, in humans, between spiritual energy and bio-chemical

energy. Through 3 interrelated approaches: spiritual, physic-chemical and

bioorganic, he was able to come up with very interesting results. He is now

proposing ways of curing the so-called incurable diseases and has developed 40

nutritional recipes for enduring good human health. He has also discovered that

the colonial formatting of the Congolese collective psycho-cultural

consciousness has had a devastating impact on Congolese general behavior. He

claims to have found ways of reformatting the Congolese collective psycho-cultural

consciousness by eradicating the effects of the colonial one. He has thus

developed therapies to heal the Congolese collective psycho-cultural

consciousness that has been marked by various successive traumas-mostly

generated by the history of capitalism.

I have experienced with some of his nutritional recipes and

have been satisfied with the results.

It has been suggested by those detecting the very high

frequencies in the human energy field,[14] that a person too focalized on material life—by extension capitalist interests—has

his or her frequencies in the lower range. A person with high spiritual

concerns has his or her frequencies in the high range. Those, for healing

purposes, who manipulate other people’s auras, with holographic universe based

techniques or forms of healing may enable us to move towards healthier social

relations conducive to new paths of development.

Longa-Seno also found that what he calls the “prets à

porter”, the ready-made-to-use cultural products have a devastating Impact on

limiting or curtailing cultural creativity. A society reduced to consumerism

will find its cultural creativity curtailed. The late N’Kanza NDolumingu and I

have been pondering why our graduates fail to acquire a spirit of discovery and

creativity in all the disciplines, more so in mathematics. The impact of the

colonial mental formatting may explain it.

Calls for African Renaissance continue to being heard. In

the hands of state officials, they have not produced meaningful results. Those

states more than not incarnate what makes such renaissance difficult if not

impossible to emerge. No African renaissance without Africa disconnecting from

the West.[15] For some time now the state per se, especially since the demise of the welfare

state, has not been a source of emancipatory politics. The continuing demand

for the unification of Africa has been part of the appeals. Berlinist states

have been unable to get rid of the colonially carved country borderlines on

which their interests rest. A Conference on the African Renaissance,[16] for example,

brought together intellectuals from the African Global Family (Africa and the

Diaspora), in 2004, its follow-up, entrusted to those states, is still being

awaited. Cheikh Anta Diopian historian Théophile Obanga, who presided over that

conference, wrote:” The pedagogy of the African Renaissance is the sole way out

for Africa not to be what she is not and to be what she must be in the world by

the year 2015.”

A new vision for Africa, of an African renewal, will not

come from the state structures. These have the desire of inclusion into the

West (Alain Badiou, The Rebirth of History.) Obenga also wrote: “Africa has

reflected, as they told her to reflect, and she has analyzed, as they told her

to analyze.” African official thinking is not free. Africa needs a lot of

thinking and analyzing; this will be meaningful only if it is done outside of

the beaten paths. In relation to economic matters Carlos Lopes[17] says a similar

thing: “Data on Africa will make sense when Africans will control both data and

the planning for investments.” We are bombarded by proclamation of high rates

of growth in Africa while there is almost nothing to indicate any Improvement

in the miserable condition of the large masses. Even in countries like the DRC

which can generate their own national budget, the budget is dependent in most

part on foreign donors. The simple element of the collection of taxes suffers

from the fact that those who are able to pay and should pay accord themselves

the privilege of being dispensed from paying taxes.

We need a lot of thinking and analyzing in Africa. “ It is

almost certain”, says Obenga,” that Africa cannot and will never develop and

consolidate, whatever one says, without a conscientized (conscientisée),

assumed and responsible vision.” Neo-liberalism and its political conditions

which stifle the possibility of generating such a vision need to be changed.

The maxim: people think and thinking is a relationship of the real requires us

to look elsewhere among the people, if the states are against such a

possibility, to discover new thinking conducive to a conceptualization of

alternative paths of development.

In the case of the DRC, I am of the opinion that if one

focuses attention on state and state related structures, one will find that the

DRC is like a body whose head has already died or dying and whose heart has

again died or dying. From the saying that the fish starts rotting from its

head; when applying it to a country, people confuse the head with the head of

state. For a country the head is constituted by, besides human heads, the

structures and institutions of intellectuality, such as schools, universities,

research organizations, think tanks, etc. In the DRC, besides the intellectual

self-abasement, those structures and institutions are collapsing. Universities,

for example, are rising in numbers but, rarely that an inspiring statement of a

new vision comes out of them. Despite the rapid growth of new churches, no real

empathy and compassion for the miseries of the broad masses of people are

expressed and practiced. Leaders of most of those churches aim at

self-enrichment and symbols of power. The thinking about the possibilities of

an endogenous social self transformation of the DRC must be searched for from

elsewhere where people are struggling for survival.

Due to the domination of vulgar materialism on the social

consciousness, due to the Impact of consumerism, creative spiritual insights

are often overlooked. The short history of the African independences, however

is, in my opinion, better explained by Simon Kimbangu’s last sermon—delivered

on September 10, 1921. The full text can be read on the internet. In summary,

he said the following points:

- Kongo and Africa will be independent; descendants of slaves will

be free and may return to the land of their ancestors;

- the first rulers of Africa won’t serve their people; they will

work for the whites;

- on the whites’ advice, they will lead their people into wars, a

lot of miseries are going to follow;

- people will forget their native languages, cultures and customs;

- young people will leave Africa in search for better places, many

will die and won’t see their parents again; they will be tempted by the white

way of living and they will learn the languages of the whites;

- this will last a long time until Black people will acquire

spiritual maturity they lost very long time ago;

- eventually a teacher will emerge to re-educate the people to

re-learn the lost languages, cultures and customs; he will be combated;

- then a divine ruler (“ntinu a yenge”) will arise with 3 powers:

the spiritual, the political and the scientific.

In conversations he had while in jail, with visitors

(priests from Kisantu in 1922 and Jean Kiansumba in 1944) prophecies

specifically related to the DRC were made. He spoke of the characteristics of

the first 4 rulers of the independent Congo, without giving names but

describing what those rules would be like and do.

With minor differences in the histories of the Berlinist

states, we can say that Kimbangu’s prophecy can pass as the paradigmatic

horizon of African history. Some earlier rulers tried to serve their people but

failed. A teacher has appeared in the DRC, others have also emerged elsewhere

calling for the recovery of African cultures. In fact, the appeal for African

renaissance seems to have been envisaged. Without going into details, we can

see that, in general terms, most of the predictions have, so far, been proven

to be accurate. Independences were granted; rulers have not been, in the main,

addressing the people’s miseries. Elements of African youth have been leaving

Africa and many dying in the sea around the Canaries island, etc. I

participated, in 2005, in a ceremony of buying back (rachat) for a returning

slave descendent from Antigua.[18]

It is somewhat tragic that people, like Mobutu, who had

knowledge of the prophecies acted almost exactly as Kimbangu had predicted:

“the second ruler will destroy the country and will remain for a long time in

power ruling with an iron fist.” One of Mobutu’s collaborators, Kitenge Yezu,

is said to have reported that in Mobutu’s circles the prophecies were known but

they did not take them seriously. Or maybe prophecies are inevitable, whether

one knows them or not.

The International Conference on Simon Kimbangu—he had

predicted himself that it would take place so that the world will know about

him—took place in Kinshasa in 2011. It drew people from all over the world—from

the USA, Cuba, Haiti, Spain, Canada, France, Belgium, Brazil, etc. I was one of

the organizers and participants.

A new cultural and spiritual awakening has, indeed, been

taking place in Africa. Through this, new orientations in thought and existence

are being spelled out. We are going to look at least three emergences.

The South African activist, Mmatshilo Motsei, in her book,

Hearing Visions, Seeing Voices,[19] tells an incredible story of great hope for Africa. She writes that on 25th May

1969, Mrs Kubelo Motsei, a domestic worker, was visited by ancestors who told

her to ready herself for an important visitor. On that day, she was in her

house and a blinding light appeared and someone entered without opening a door.

She was frightened and was trembling. The visitor identified himself as Jesus

Christ now assuming the name Rara Konyana. He asked her not to be afraid. He

told her that she was chosen by the Holy Spirit to become the path through

which Africa will rise again. He told her about the dawning of the Third World;

the time of the reclamation of African spirituality and the return of the Holy

Spirit to Africa to heal and spiritually liberate all people of African descent

had come. In the new century, the world would turn to Africa for guidance. New

knowledge and a spiritual curriculum would be developed by the ancestors of all

races and religions. The sick would be nursed back to physical, emotional and

spiritual health by the ancient healers of Africa, visible and invisible, as well

as by Western healers led by the compassionate healing power of Florence

Nightingale. With time, the Spirits would heal the world and communicate

through a black person, and a woman, Mrs Kubelo Motsei whose name now changed

to Mother Toloki.

A time of healing for Africa has come. “…the ancestors will

encourage and make possible surgical operations that do not involve cutting the

body.” In this era, called the African century, the gift is assigned to Africa—by

the Voice.

Mother Toloki received powers to communicate directly with

the ancestors and to see them. She eventually created a spiritual place where

teaching and healing take place. The key message she has been spreading is the

restoration of self-pride through, among other things, art forms and culture.

Those interested can read the book.

About the same time, in 1969, an engineering student in the

DRC, Zacharie Badiengila, was visited by a very tall man telling him that he

has been selected to continue the work Simon Kimbangu had started but not finished

and to rescue it from its present deviation by, among others, churches created

in the name of Kimbangu that retain him as an idol but not his ideals.

Badiengila has since formed a kind of traditional church, Bundu dia Kongo,

providing moral training to would-be politicians, working very hard to recover

and teach Kikongo language and Kongo culture to those who have forgotten them

as well as those who are interested. He has produced a tremendous amount of

documents on various subjects related to spirituality, religion and sciences

His name was also changed to Nlongi Ne Muanda Nsemi. I cannot go into details;

I wrote an article on his church, Bundu dia Kongo, interested people should

read.[20]

Between 1998 and 2003 a group of young women emerged as

spiritual healers, in an area where medical facilities were either impoverished

or inexistent. The most known ones, Lukombo and Jeanne, were working at

Kingwala village (in the territory of Luozi, in the DRC). They performed, among

other things, spiritual surgical operations and they would climb mysteriously

to the summit of palm trees to get spiritual medicine. I was diagnosed with the

spiritual stick used and was treated by Jeanne.

Recently in Congo/Brazzaville has arisen an important

movement, spiritually inspired, of the restoration of Kingunza, the traditional

religion in ancient Kongo kingdom. A new message has been received through

revelation by the ngunza Auguste Tsula-Mazinga Mlolo. (7volumes) It is a kind

of travel warrant or spiritual road map for the process of liberation, in the

area that was ancient Kongo kingdom, still not free spiritually, politically

and scientifically. It is a spiritual cleansing that is called for as a

preparation for the self-liberation of the descendants of the Kongo Kingdom. A

Universal Temple to spread Kingunza in the world has been created and it has

the leading core in France, under the leadership of ngunza Antoine Nkoyi Ngoka.

This is the first organization to have started to present systematically the

doctrine of Kingunza Kikulu, as reactivated in the revealed book of Mazinga

Mlolo. Some of the notions which have been used in previous ngunza groups get

here a systematic treatment. The first volume of the book can be found on the

internet.[21] One can also find there important prophecies made by ngunza Ngoka concerning

the whole world in general and the Mbanza Kongo living space (everywhere Bena

Kongo people live) in particular.

All the above indications are just to show that even at the

spiritual level, different paths are being acclaimed and the restoration of

African cultures are said to be the basis—even if new cultural elements are

also produced. This call to return to the sources has variants; but, in most

cases; it is selective and critical of bad traditions such as witchcraft and

other destructive practices which have contributed to destroy African

principles such as botho/ubuntu—founded on values of mutual support, sharing,

interdependence, as opposed to egoism.

In line with those trends of African renewal, are also

re-activated forms of socio-political organizations of community healing, for

example, which emerged throughout the history of struggles against slave trade,

colonialism and the need for re-asserting the human dignity of the “most

humiliated race in the world”(Simon Kimbangu). One could mention, in the Mbanza

Kongo living space: Mbongi and Lemba.

Mbongi-also called Yemba, Boko, Lusanga—was an institutional

site where people in each community gathered, around a fire, and all the

exchanges over individual or collective daily experiences took place. It was

some kind of site for collective/individual thinking, planning, living and

acting. Anybody was free to come to Mbongi. Anybody capable of speech was in

principle allowed to speak. Even the strangers were welcome to Mbongi; but,

they were reminded of the proverb: “eat, drink and go home for you don’t know

how the village was built.” One came to Mbongi with whatever one was able to

bring: a piece of wood for the fire, peanuts, a cassava root… or one just

brought one’s body and especially the mind to share in the conversation. No one

was excluded on grounds of not bringing anything to Mbongi. The adults wished

that the kids bring wood; they did not chase them if they did not bring wood.

It was at the same time a kind of school. This is where the

male children learned most of the customs and culture. Men mostly participated;

but there were moments when women did come to Mbongi. Women in the community

send to Mbongi their husbands’ food. Men ate together. Unfortunately, the adults

ate the lion’s share and gave to male children the leftover. Food sharing was

also an occasion for moral education. “The child who obeys never goes hungry,”

and “if you are eating, you must look around you, for someone who is not

eating. Someday, he or she will be eating and it will be too late for you to be

wise;” those are proverbs one hears said.

In Kinshasa, we tried to extend the notion of Mbongi to aim

at the whole country and develop it as a new kind of political subject—correcting

the shortcomings or the breakdown of the political party. The Mbongi a Nsi—the

country’s Mbongi—was also open to everyone who desired to come there and

everybody spoke in their own names. The maxim that “people think and thinking

is a relationship to reality” was our basis for not refusing thinking to

anyone. Terms of reference were given to every participant and discussions

started around those terms. As in a traditional Mbongi the aim was, among

others, to arrive at principles which are good to all on which to base further

collective action. The state functions on the assumption that people don’t

think—especially not politics; only the state recognized/certified people

should think. The ultimate objective for us is to create a space of freedom and

expose the state space of command.

On the occasions of community events, Mbongi sits as a

palaver; its process is marked by the nature of the events. Those events are

often violations of the fundamentals of functioning of the community. These

include: sharing as opposed to competition, the legal traditional “law”(nkingu)

that aims at reconciling contestants in a conflict rather than making one right

and the other wrong, and sustainability in relation to the land, the ancestors,

to each other. The process is one of resolution of contradictions among the

people; it is a form of popular politics and at the same time a process of

community healing, learning and educating.[22] The idea is not just to get the accused to confess, but it is to cleanse him or

her and to also cleanse the community which made it possible for something bad

to happen through a member of the community. The palaver must end with a

generalized community enthusiasm. Otherwise, contradictions among the people

have not been resolved. Defensive prescriptions are heard: open wide your eyes

and ears and shut your mouth. Until another round of palaver takes place. The

militant of Mbongi intellectuality, focused on revealing truth and eradicating

confusion and clarifying or simplifying the speech, is called Nzonzi—a master

of speaking, symboling and spiritual massage, a dialectician. He knows when to

sing the appropriate song, to cite the appropriate proverb, to keep the talking

going.

I cannot go into details here. I mentioned this experience

as a possibility in the opening up of new forms of conceptualization of

emancipatory politics.

Lemba movement emerged as the slave trade-devastated

society’s response for its reconstruction; it is not a state based movement—as

the crumbling state had become unable to represent or defend the people.

Society had to be reconstituted and made livable; the family had to be

recreated and given the needed social massage for the desire to have children

to arise again. Slave trade has made it almost impossible to desire having

them. The extended family had to be cured of afflictions. The individual had to

develop self-esteem again and confidence. People who have been running, hiding

in forests had now to come back to form villages. It is more than therapeutic

techniques; it is rebuilding society to make human dignity meaningful again.

Lessons drawn from this process of social healing should be important for any

politics of peace. Lemba was conceptualized as “mukisi wa mfunisina kanda”—“a

knowledge and practice of re-peopling the clan.”

Initially, in the ancient Kongo kingdom, Lemba was one of

the 3 cultural pillars: Spirituality (Kimpeve), Polity (Kimayala) and

Scientificity (Kimazayu). Lemba organized Kimazayu.

In a sense, it is a sign of arrogance to think that people

who have passed through or endured the worst inhumane situations will have

nothing serious to contribute to humanity. And this is perhaps the rationale of

the message delivered to Mother Toloki: those who have suffered the most shall

be the teachers of tomorrow for the world to achieve the needed change to make

it be of less suffering.

I tried in this short paper to point out some of the reasons

why Africa must retain, once again, and much more so than before, alternative

paths of development as an option or perhaps the only option. The general trend

of world development points toward new paths of development as condition for

the survival of humanity.

Africa does have plenty of natural resources; she is also

rich in cultural and spiritual resources that could enable her to move away from

the Western conception of politics as a form of war and towards a politics of

peace. Africa will develop on her own as she is and should be. Only through an

alternative path of development will this happen. Social forces are

accumulating to break down the resistance of those who desire to be included in

the West. The failure of existing states to act in tune with people’s miseries

and combats and develop creative forms of resource sharing will increasingly

make them be obsolete.

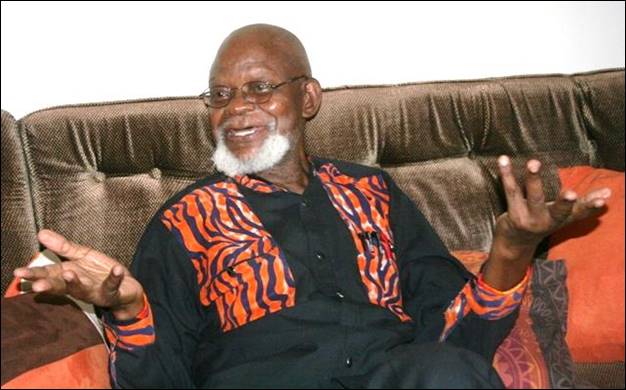

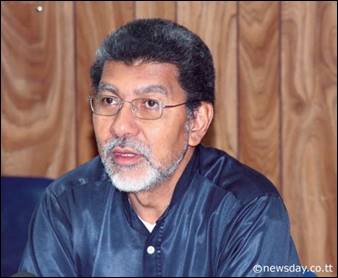

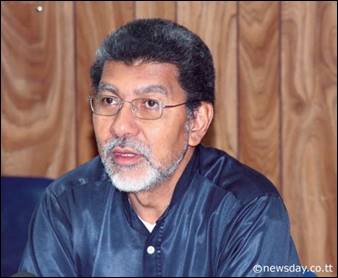

04 The Caribbean: Fifty years after political

independence, a promise unfulfilled by David Abdulah

[23]

Photo courtesy of Newsday in Trinidad and Tobago.

Photo courtesy of Newsday in Trinidad and Tobago.

Political independence

August is an important month in the calendar of the English

speaking Caribbean. It was on August 1st, 1838 that slavery was finally ended